Since I’ve begun this journey on speaking up for wheat, many people have criticized me in doing so. Why in the world would I stand up for a product that has been deemed by many to be “toxic” and “unhealthy”?

Well here’s why. Wheat matters. It matters locally, it matters nation-wide, and more importantly it matters globally.

It is extremely easy for all of us to sit here and be critical of a product that we think doesn’t affect our day-to-day lives. But the truth is that it does. Wheat affects our lives, whether we like it or not.

Last week we looked at how wheat matters on a local, state level. This week, I’d like to talk about why wheat matters on a nation-wide level. And eventually with part three I will encompass wheat on a global scale.

1. Wheat Has an Important Legacy

Wheat first entered into the United States primarily as a hobby crop. It is said that George Washington was one of the first people to grow wheat. Either way, wheat production was difficult in New England and much of the colonial South. This fact made wheat flour entirely too expensive for regular use. High transportation costs made long-distance transport of wheat from regions better suited to grow it unfeasible. During this period (1600s and 1700s), colonists grew other crops, especially corn, and wheat flour was left to the wealthy consumers.

However in the 18th century, thanks to technology, wheat became more readily available to the general consumer. Oliver Evans developed an improved milling system in 1790 that reduced the labor needed in a mill by more than half while increasing the flour extraction rate from wheat. John Deere developed a steel plow in 1837 which reduced production costs and stimulated wheat production by greatly increasing the rate at which soils could be tilled. In addition to technological improvements, transportation infrastructure helped reduce flour cost to U.S. consumers. At mid-century, rail transport was 1/10th the cost of hauling grain overland by road.

It was during the 19th century that wheat production exploded in the United States. Up until then, nearly all U.S. wheat production consisted of soft wheat varieties. A hard spring wheat variety with higher protein content was introduced in Minnesota in the mid-1800s. Expansion of the railroad westward allowed this hard spring wheat variety to move east in the late 1800s. Durum wheat production begin in 1904 in North Dakota and Mennonites brought with them a hard winter wheat variety to Kansas. The wheat production landscape as we see today was taking shape.

Today wheat is grown in 42 of our 50 states with production predominantly throughout the Plains. States such as North Dakota, Kansas, Montana, South Dakota, and Texas reign supreme when it comes to wheat production. The top ten states account for nearly 72% of all wheat production in the United States. Wheat is the third largest field crop produced in the United States behind corn and soybeans. According to the last census of Agriculture, the wheat industry accounted for 3.6% of all agricultural products sold and 7.2% of all farms in the United States. That 7% of farms equals over 250,000 farms growing wheat across the nation.

2. Wheat Is Important to the Economy

The United States may seem like a major wheat producer, but worldwide we rank behind China, the European Union, and India. In 2011, U.S. wheat production represented almost 8% of the world total. U.S. Wheat Production is, however, very unique. We produce all six classes of wheat as well as can export all six classes of wheat. This makes us a reliable supplier in the world wheat market.

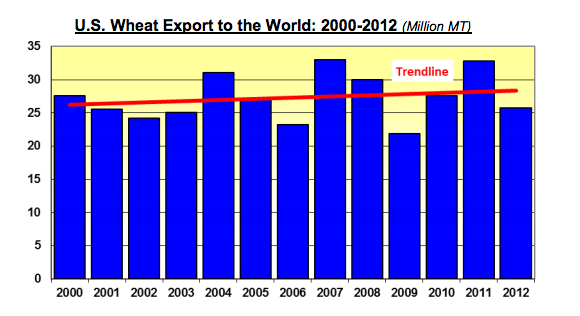

We may not be the largest wheat producer, but the U.S. is consistently the world’s largest wheat exporter, exporting nearly 42% of its annual wheat production. In 2010, wheat exports contributed nearly $5.9 billion to the U.S. economy. The largest destinations for U.S. wheat are sub-Saharan Africa, Japan, Mexico, and the Philippines. In 2011, U.S. ending wheat stock represented about 11% of world ending wheat stocks.

3. Wheat Acres Are Declining

So it may seem like wheat production is booming here in the United States. But the truth is that wheat is often been deemed, “the most overlooked commodity produced in the U.S.” U.S. wheat acreage continues to be pressured by a variety of factors. Increased demand for crops like corn and soybeans has caused wheat acreage in the Upper Midwest (particularly the Dakotas and Kansas) to be shifted into corn and soybean production. In the early 1980’s wheat accounted for 80-90 percent of the total wheat, corn, and soybeans planted in the top two wheat-producing states, Kansas and North Dakota. Now, USDA reports in recent years wheat’s share has dropped to about half of the this three-crop total.

We see this is especially true in our area in North Dakota. Before Round Up ready soybeans were available to farmers, soybeans weren’t really grown here or on our farm. Now every year soybean acres grow both state-wide and nationally. In 2014, USDA predicted record soybean acres planted.

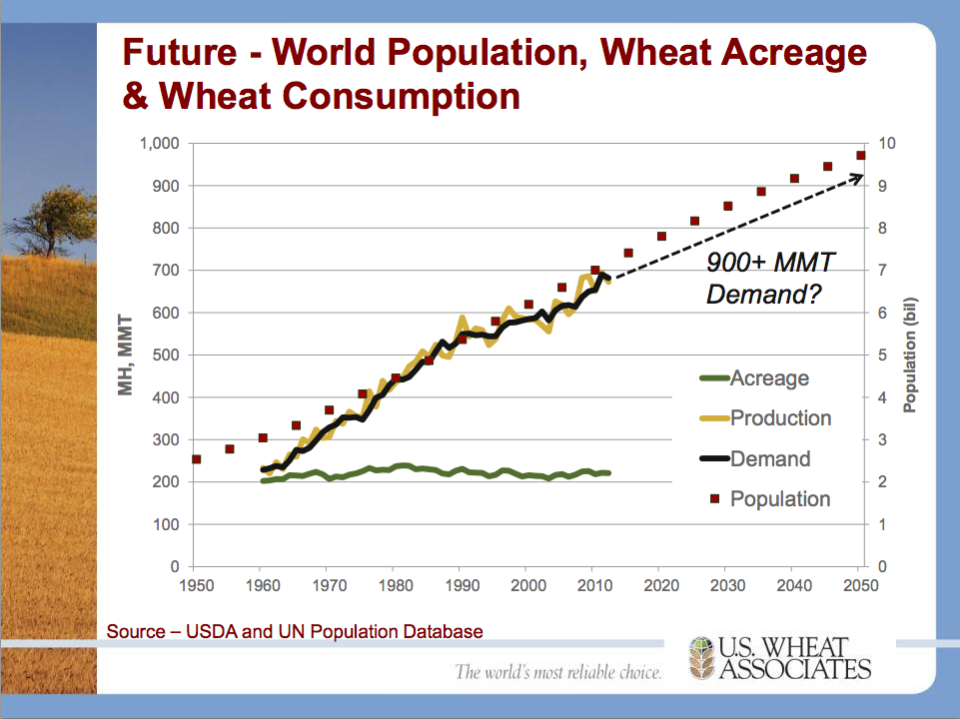

While this may not seem like a big deal, especially considering that the U.S. produces about 8% of the world wheat total, the world wheat market is expanding. We are starting to experience a new era in wheat production that brings with it, a three-part problem. First, wheat acres are declining and the U.S. exports nearly half of what it produces. Second, as populations increase in places where we currently export wheat, demand will also increase. Third, in addition to traditional global competitors, Russia and the Ukraine have emerged as new competition. As a result, USDA projects a smaller U.S. share of this expanding world wheat trade market. These three things are important factors in defining the future of our wheat production in the United States.

4. Wheat Research is Imperative

U.S. Wheat feeding a growing population is a topic that has been on the minds of many in the wheat industry. And allowing the technology necessary for farmers to continue to produce more, with less acres is imperative. Historically, the amount of funding dedicated to wheat research has been dwarfed by the funding dedicated to other major crops. Many are calling for an increase in public and private research to sustain a world population with wheat.

The movement to row crops such as corn and soybeans throughout the Plains reflects the rapid pace of technology and genetic adaptations in these crops. New varieties of these crops can now be planted in places they never were able to be planted before, such as farther west and north in climates with drier conditions or shorter growing seasons. However, the pace of genetic improvement has been slower for wheat, resulting in slower growth in wheat yields. This can make wheat a less attractive cropping option for many farmers.

The genetic improvements for wheat has been slower due to two different factors: first, genetic complexity of wheat and second, there are lower potential returns to commercial seed companies. It is common practice for many wheat farmers to use saved seed from previous year’s crop instead of buying it from dealers every year. This practice greatly reduces the potential market for branded commercial seed and thus reduces development in seed research. The ability for seed companies to sell seed every year generates returns to invest in needed breeding programs to develop new varieties.

5. Wheat Grown in the U.S. Affects Far Beyond our Borders

Although Wheat is planted almost every day somewhere in the World, the United States has the resources and infrastructure to provide an abundant and reliable supply of wheat domestically and to the world. By 2050, the World Population is expected to jump from 6.8 billion to 9.5 billion, with most of the growth concentrated in places that we currently export wheat to. With wheat accounting for 20% of all calories consumed worldwide, we are going to need all of us. But especially the top exporter of wheat worldwide, the United States. It is going to require the work of farmers, seed companies, scientists, and researchers in this country working together to provide one of the most economical, plentiful, and nutritious groups of food available to those 9.5 billion people worldwide.

You may not choose or require wheat in your diet, but the truth is the wheat grown here in the United States does feed someone else’s hungry mouth. And while it is easy to be critical of an industry in your backyard while your belly is full, there are many out there who don’t know where their next meal will be coming from. Just some food for thought.

Resources

Brester, G. (2012). Wheat Overview.

Englund, R. (2013). History of Wheat.

Liefert, O. (2013). USDA: U.S. Wheat Trade

Lusk, J. & Miller, H. (2014). We Need GMO Wheat.

Matz, M. & O'Connor, M. (2015). Wheat: The Staff of Life.

Minnesota Department of Agricultre. (2013). Why the Export Market is Important for U.S. Wheat

Oades, J. (2014). Biotech Wheat: Part of the Future

Vocke, S. & Liefert, O. (2014). USDA Wheat Baseline 2014-23

Young, K. & Honig, L. (2014). U.S. Farmers Expect to Plant Record-High Soybean Acreage

Jenny, thanks for your calm, reasonable defense of agriculture and wheat in particular. I just hope that the people who need to be reading your posts are actually doing so! They must be if you are getting negative comments. Keep up the good work!